With the end of Justice Michael Gableman’s term approaching, and the election of his successor just two weeks away, SCOWstats takes this opportunity to explore some of the consequences of his victory over Justice Louis Butler in 2008. Although discussion of the bitter and controversial campaign faded eventually, the significance of the election did not, for it transformed the supreme court’s voting much more than did the replacement of Justice Wilcox by Justice Ziegler the previous year. We’ll utilize data for the period 2004-05 through 2014-15—when the court’s membership remained unchanged other than the Butler/Gableman and the Wilcox/Ziegler substitutions—and observe some of the effects that an election can have.

The isolation of Justices Abrahamson and Bradley

Let’s begin by examining the frequency with which each of the nine justices voted in the majority. During the four Butler terms (2004-05 through 2007-08) Justices Abrahamson and Bradley appeared in the majority as regularly as the other justices, all of whose percentages in the majority clustered tightly between 80% and 86% (except for Justice Crooks), as shown in Table 1.[1] That changed dramatically after Justice Gableman ousted Justice Butler. During the seven Gableman terms (2008-09 through 2014-15), Justices Crooks, Prosser, Roggensack, Ziegler, and Gableman all joined majorities at a very high (and nearly identical) rate—between 90% and 94%—while the figures for Justices Abrahamson (59%) and Bradley (64%) dropped markedly.

(click on tables to enlarge them)

The change is even more striking if we consider only non-unanimous decisions (Table 2).[2] Once again, Justice Abrahamson and Justice Bradley figured in majorities during the Butler years at rates comparable to those of their colleagues (other than Justice Crooks)—indeed, Justice Bradley voted with the majority more often than any other justice except Crooks, just as she did in Table 1. But during the Gableman years, Justice Abrahamson (27%) and Justice Bradley (35%) vanished from most majorities, while every one of the five other justices remained in majorities at least 83% of the time in these non-unanimous decisions.

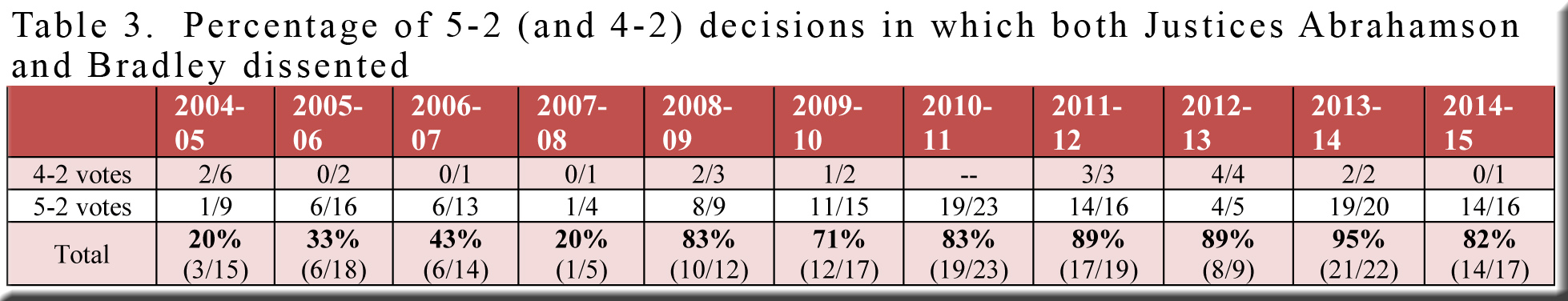

Another indication of how marginalized Justices Abrahamson and Bradley became (or, to put it another way, how polarized the court became) is the enormous increase in the rate at which these two justices accounted for both of the dissenting votes in 5-2 (and 4-2) decisions after Justice Gableman supplanted Justice Butler. During the four Butler years, Justices Abrahamson and Bradley provided the two dissenting votes in only 31% (16/52) of these cases, and they did not find themselves more isolated in this respect after Justice Ziegler replaced Justice Wilcox for the last of the Butler years. The following year (2008-09), when Justice Gableman joined the court, Justices Abrahamson and Bradley were the sole dissenters in fully 83% of 5-2 (and 4-2) decisions—and their average for all seven Gableman years was 85% (101/119), as detailed in Table 3.

These new voting patterns not only polarized the court, they altered its rulings on various issues. Although it is beyond the scope of this project to examine all of the numerous categories of cases heard by the justices, we can offer some comparisons involving types of cases previously investigated by SCOWstats. If readers familiar with cases of other sorts have sensed a change (or lack of change) produced by the Butler-Gableman transition, I would be grateful to learn of these impressions.

All criminal cases

Table 4 indicates that a number of justices (most notably Justice Crooks) were somewhat less likely to accept defendants’ arguments during the Gableman years than during the Butler years, which admits the possibility that the court might have grown a little tougher on defendants even without the arrival of Justice Gableman.[3] However, the shift in the voting of these justices was far less dramatic than the difference between the votes cast by Justice Butler (who favored defendants in 48% of such cases) and Justice Gableman (for whom the figure was only 10%).

Thus, although the court may have been growing less receptive to defendants’ arguments even without Justice Gableman (Table 5), his replacement of Justice Butler would appear to be an essential factor in explaining the 50% drop in the rate at which the court’s rulings favored defendants during the Gableman years (14%) compared to the Butler years (28%).

Sixth Amendment cases

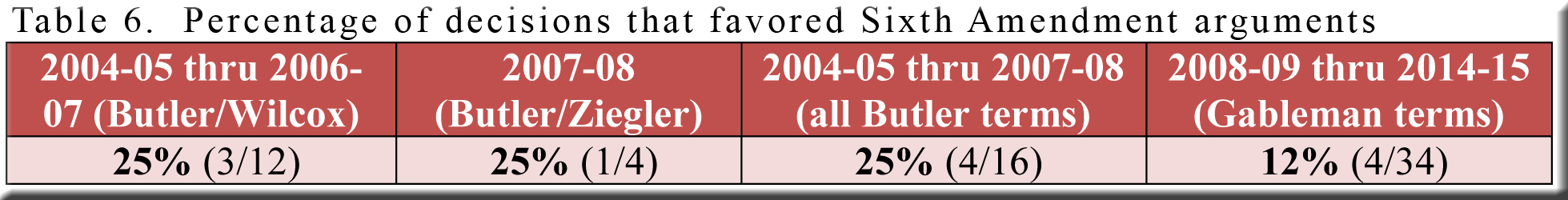

Here, too, the court favored defendants’ arguments twice as frequently (25%) during the Butler years as it did during the Gableman years (12%). Moreover, with regard to Sixth Amendment arguments, the justices were no less sympathetic at the end of the Butler years (when Justice Ziegler had succeeded Justice Wilcox) than they were at the beginning. The entire change occurred following the replacement of Justice Butler by Justice Gableman, as shown in Table 6.[4]

While some other justices favored Sixth Amendment arguments less often during the Gableman years than they had previously (Table 7), the difference was not nearly as great as that produced by the substitution of Justice Gableman (who accepted Sixth Amendment arguments in only 3% of cases) for Justice Butler (44%). Clearly, this change was vital in explaining the drop from 25% to 12% in the last two columns of Table 6.

Fourth Amendment cases

Similar to the fate experienced by Sixth Amendment arguments, the rate at which the justices accepted Fourth Amendment arguments declined by roughly 50% when the court moved from the Butler years to the Gableman years, as displayed in Table 8. And, as with Sixth Amendment cases, the change did not commence when Justice Ziegler joined the court following the retirement of Justice Wilcox, who was even less well-disposed to Fourth Amendment arguments than she has been.[5]

Comparing the votes cast by individual justices over the Butler-Gableman divide (Table 9), we find that some (including Justice Abrahamson) were less amenable to Fourth Amendment arguments in 2008-09 through 2014-15 than they had been during the four preceding terms. But, once again, by far the biggest change occurred when Justice Butler (who accepted Fourth Amendment arguments 67% of the time) yielded his seat to Justice Gableman, whose approval rate of Fourth Amendment arguments was only 5%.

Insurance cases

SCOWstats has accumulated less information on civil cases over the years, but enough is at hand regarding insurance disputes to permit some observations. First, as in the criminal cases covered above, the votes by Justices Butler and Gableman differed conspicuously. In litigation pitting claimants against insurance companies, Justice Butler sided with insurance companies 28% of the time—far less often than Justice Gableman, who favored insurance companies in 68% of such cases. In fact, Table 10 finds Justice Butler among the least inclined (along with Justices Abrahamson and Bradley) to accept the arguments of insurance companies, while Justice Gableman deemed these arguments persuasive more regularly than did any other justice.

This suggests that the court grew more willing to side with insurance companies after 2008, and such was indeed the case. After favoring insurance companies 44% of the time during the Butler years, the justices ruled for the companies in 51% of their cases thereafter (Table 11). One should note the unusually high rate (89%) at which Justice Ziegler accepted insurance companies’ arguments during her first year on the bench, which reduced the size of the gap between the Butler and Gableman periods. If Justice Ziegler had continued to align with insurance companies at this rate after her initial term, there would be grounds for asserting that—in insurance cases, at least—her replacement of Justice Wilcox was just as pivotal as the Butler/Gableman succession. However, we have a much larger sample of Justice Ziegler’s votes from the Gableman years, when she favored insurance companies 59% of the time (Table 10). This more representative figure not only positions her in the same neighborhood as her conservative colleagues, it also moves her much closer to her predecessor, Justice Wilcox (52%). Thus, yet again, the unseating of Justice Butler by Justice Gableman emerges as the most compelling factor in explaining a change in the court’s decisions.

Conclusion

Whether the difference made by Justice Gableman’s defeat of Justice Butler is cause for rhapsody or despair depends on one’s point of view, of course, but I doubt that anyone would deny its significance. This post supports the conclusion that when a Wisconsin electoral campaign produces a change in office of just one person, only the advent of a new governor is likely to have a greater impact on citizens than does the election of a supreme court justice whose views clash with those of his/her predecessor. The massive campaign contributions now routine in supreme court races demonstrate that wealthy donors have grasped this point, whereas the low turnouts in these April elections intimate that most voters have not.

Meanwhile, a recent Marquette Law School poll found that approximately 80% of registered voters had not formed an opinion (favorable or unfavorable) about either of the two candidates vying to replace Justice Gableman—even after the primary election, and only a month before the final ballot. Readers with a dogged sense of optimism will presume that the handful of citizens with some awareness of the two candidates are the same handful who will venture to the polls, but others may prefer a variation on an old joke: “—The pool of prospective voters is woefully uninformed. —Yes, and what’s more, hardly any of them will bother to vote.”

[1] Click here for a table that provides figures for every individual year.

[2] Click here for a table that provides figures on non-unanimous decisions for every individual year.

[3] Of course, one might hypothesize that the success of the “soft-on-crime” attack employed by future-Justice Gableman to unseat Justice Butler might have contributed, if only subconsciously, to the harder line taken after 2008 by some of the other justices. However, it certainly did not have this effect on Justices Abrahamson and Bradley, and, in any case, this speculation is impossible to substantiate.

[4] Given the small number of cases yielded by a single term, one should regard with caution the figure for 2007-08 in Table 6 (and Table 8).

[5] For a comparison of the votes by Justices Wilcox and Ziegler in Fourth Amendment cases over a longer period of time, click here.

Speak Your Mind